Tyrants at the Gate

In business, in politics — they can be found everywhere

“A king rules over willing subjects, a tyrant over unwilling.”

— George Buchanan, 1579

I’ve been thinking a lot about authoritarians lately.

Maybe you have, too.

Call them autocrats, despots, strongmen, bullies, dictators, oppressors, tyrants — the names may differ, but their behaviors are the same.

I know you didn’t sign up for this newsletter for political commentary. Anyway, this is less political commentary than it is leadership commentary.

Observations about certain tendencies of human nature that have played out over the centuries and across the continents, time and again.

There are forces afoot that affect all facets of our lives, from human rights to business regulations — forces that are bound up in a kind of dyspeptic and despotic leadership that increasingly pervades our existing systems.

And our job here is to draw lessons from them.

There are tyrants from the long past, like Julius Caesar and Napoleon, as well as from the last century and recent past, such as Fransisco Franco, Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Idi Amin, Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi, Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, and others.

And we see our fair of strongmen in the present: Jair Bolsonaro, Rodrigo Duterte, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Viktor Orbán, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump (and other fast followers in the Chaos Caucus).

If you’ve spent any time in the workplace, you probably recognize similar traits that emerge from similar personalities:

Abuse of power 💥

Bullying 💪

Divisiveness 😡

Selfishness 🤳

Narcissism 🪞

Deception 🤥

Control dynamics 🦸

And that’s really what the tyrant or strongman is all about: control.

We’ve seen it repeatedly: the need to control and exploit others, typically done for personal gain—power and enrichment.

So the questions for today are: how can we identify some of their characteristics? And more importantly, what can we do once we know they’re a threat?

Related: previous Timeless & Timely posts:

There are two books that pointed me in this direction: Strongmen: Mussolini to the Present by Ruth Ben-Ghiat and Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics by Stephen Greenblatt. I’ll be referring to each. And of course, there’s another book in the Recommendations section below.

Times of Upheaval

No one likes uncertainty.

It’s unsettling and leaves people looking for answers, sometimes where there are none to be had.

Shakespeare had a way of addressing these concerns, but in a sort of code:

“Under what circumstances, Shakespeare asked himself, do cherished institutions, seemingly deep-rooted and impregnable, prove fragile? Why do large numbers of people knowingly accept being lied to? How does a figure like Richard III or Macbeth ascend to the throne? Why would anyone, he asked himself, be drawn to a leader so manifestly unsuited to govern, someone dangerously impulsive or viciously conniving or indifferent to the truth?” (Greenblatt, p. 2)

We see these tendencies in the characters of Macbeth, Lear, Richard III, Caesar, Coriolanus, and others. Shakespeare used oblique angles to criticize contemporary leadership, lest his head end up on the chopping block. But the meaning was clear: his literary figures stood in for contemporary leadership.

Looking over the developments of the last century, we find a similar theme:

“For one hundred years, charismatic leaders have found favor at moments of uncertainty and transition. Often coming from outside the political system, they create new movements, forge new alliances, and communicate with their followers in original ways. Authoritarians hold appeal when society is polarized, or divided into two opposing ideological camps, which is why they do all they can to exacerbate strife. Periods of progress in gender, labor, or racial emancipation have also been fertile terrain for openly racist and sexist aspirants to office, who soothe fears of the loss of male domination and class privilege and the end of White Christian "civilization."” (Ben-Ghiat, p. 8)

When things are uncertain, the autocrat seeks not to unite, but to divide. To name enemies and to turn the populace against itself.

A Walking Contradiction

And in such moments, it becomes natural to doubt our own judgment. Just as natural is the willingness to turn to leaders to answer our needs or solve our problems.

With the seed of self-doubt planted and the requirement of self-reliance lifted, we’re then willing to believe even the most ridiculous and illogical contradictions.

“The strongman’s rogue nature also draws people to him. He proclaims law-and-order rule, yet enables lawlessness. This paradox becomes official policy as government evolves into a criminal enterprise.” (Ben-Ghiat, p. 251)

“The strongman’s trick is to seem exceptional and yet to embody the national everyman, with all of his endearing flaws…The familiarity of these personages, marketed by their personality cults and populist ideologies as “one of us,” is also why many people don’t see them as dangerous early on.” (ibid, 252)

Maybe they do things that seem impulsive — perhaps they crave chaos that drives attention (such as chaos man/child Elon Musk). This is designed to keep you off balance and outraged, so you’re distracted from addressing anything of substance.

Based in Fear

When times are uncertain, we naturally fear the unknown. Franklin D. Roosevelt reminded us, in 1933 as America struggled with the Great Depression, “that the only thing we have to fear is...fear itself.”

“It is [fear] that makes people so willing to follow brash, strong-looking demagogues...capable of cleansing the world of the vague, the weak, the uncertain, the evil. Ah, to give oneself over to their direction—what calm, what relief.” — Ernest Becker, 1962

Strongmen stoke fears, whether it’s through exaggerating the speed of a competitor’s product development, fanciful caravans of foreigners (an Orbán favorite), or non-existent classroom curricula.

These fears are designed to elicit a knee-jerk response that is devoid of thinking, fueled only by anger and hatred.

“Hatred is the most accessible and comprehensive of all the unifying agents.” — Eric Hoffer, 1951

Hate is a powerful motivator — one that is universally employed by tyrants.

Interestingly, they eventually fall prey to their own fearmongering. They become fearful and paranoid (think of Putin and his comically long table, with no one allowed near him).

According to Ben-Ghiat, this has always been the case with strongmen, as “their isolation, suspicion, and anger, often conjoined to an arrogant overconfidence, hastened their downfall.”

Lack of Empathy

One of the hallmarks of a good leader is the presence of empathy and emotional intelligence. But in the authoritarian, the opposite is true.

Mussolini told a journalist that the secret to his success was “Keep your heart a desert.” In 1941, Italian filmmaker Alberto Lattuada, who grew up under the regime, captured it perfectly:

“The absence of love brought many tragedies that might have been averted. Instead of the golden rain of love, a black cloak of indifference fell upon the people. And thus people have lost the eyes of love and can no longer see clearly. . . . Here are the origins of the disnintegration of all values and the destruction and sterilization of conscience.” (Ben-Ghiat, p. 259)

In Richard III, the titular character was physically and emotionally twisted, willing to eliminate anyone who stood in the way of his quest for the crown. He had no compunction about harming others, no doubt stemming from his lack of empathy, which he freely admitted:

“Tear-falling pity dwells not in this eye.” (Act IV, Scene 2)

Empathy is, by far, an essential element in good leadership. Without it, employees, customers, and even communities are treated with disdain — as components of a transaction.

I coach up-and-coming leaders on empathy-based leadership skills. More about my advisory services:

Incompetence

When the only goal for an autocrat is the attainment of power, it shouldn’t be too surprising to know that when he does achieve his goal, he’s incapable of leading.

“Although we often hear that strongmen are genius strategists, few, if any, of them had a master plan for their rule.” (Ben-Ghiat, p. 222)

Brought to life perfectly in Richard III:

“But once Richard reaches his lifelong goal—at the end of the third act of Shakespeare's play—the laughter quickly begins to curdle. Much of the pleasure of his winning derived from its wild improbability. Now the prospect of endless winning proves to be a grotesque delusion. Though he has seemed a miracle of dark efficiency, Richard is quite unprepared to unite and run a whole country.” (Greenblatt, p. 84)

It’s like an executive who excels in crisis management who, suddenly devoid of crises to manage, finds himself in unfamiliar territory in more strategic or even day-to-day management.

In some cases, these kinds of leaders will manufacture their own mini-crises or fire drills for their teams, swooping in to solve things themselves. Crisis averted, hero saves the day.

Finding (and Being) a Non-Tyrannical Leader

One of the first steps to avoid such behavior is to surround yourself with strong team members.

While tyrants don't like to be questioned, the emotionally intelligent leader is comfortable being challenged by people who have complementary strengths. Asking questions leads to better answers, both for our colleagues and for ourselves.

What should you do if you find yourself in a situation where there is mindless adherence to a process or a leader, where commands are barked and no one is allowed to question the leader or deliver bad news?

You can ignore it and put up with it (temporarily, as you should be eying an exit); you can stand up for yourself (something bullies typically back down from); or simply get out.

Your actions may inspire similar reactions around you—that is, your colleagues may find strength in you leading by example.

When the warning signs are apparent, know that you have the power to do something about it.

In some cases, you may be the last line of defense against an oppressor.

“Corruption’s not of modern date;

It hath been tried in every state.” — John Gay, 1731

The Memory of a Great Man

When Beethoven originally wrote his Third Symphony (the “Eroica”) in 1803, he dedicated it to Napoleon, inspired by his virtuous ideals of independence and opportunity. But when Napoleon crowned himself emperor the following year, Beethoven violently erased Napoleon’s name from his manuscript—so forcefully, in fact, that he erased his way right through the paper, leaving holes in the title page. He instead dedicated it “to the memory of a great man” — the man Napoleon had once been. (PBS)

Brave New Technology

A warning from Aldous Huxley of the potential for dictators and would-be dictators to exploit emerging technologies to produce propaganda. (Aeon)

Freedom from Tyranny

How a cult was built around a political ideal in Ancient Greece. (Lapham’s Quarterly)

“And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed—if all records told the same tale—then the lie passed into history and became truth. ‘Who controls the past’ ran the Party slogan, ‘controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’” — George Orwell, 1949

Advantage, Zelensky

A study out today from political scientists Ryan Grauer and Dominic Tierney reveals why democracies have an advantage over authoritarians in war. The sharing of power across officials in the legislature, judiciary, and executive branches means there is more open debate, reducing the chance of unpopular wars and, by extension, bad decisions. (Letters from an American)

I Think, Therefore I Change My Mind

Assuming that another person’s opinions are immune from criticism is not a marker of respect. It is, in fact, dehumanizing. “The worst tyrants demand not just to be obeyed but to be treated as incapable of error in every deed and saying… A person whose choices can never be mistaken cannot really have any meaningful plans or objectives, only a series of impulses.” (Aeon)

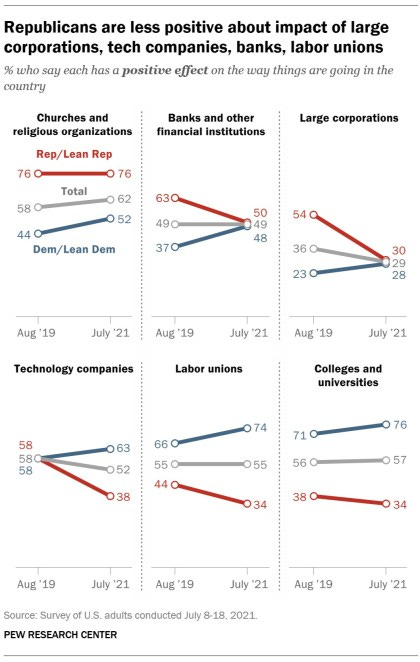

Who Will Save Us?

Republicans have focused on destroying faith in building blocks of civil society: education, law enforcement, press, financial institutions, business. And now — surprise, surprise — their trust is eroding in big corporations, technology companies, banks, labor unions, and colleges and universities. The one area where their trust remains high? In churches. It’s the Autocracy Playbook: destroy institutions so only a strongman can save us, with a dash of theocracy on the side. (Pew Research)

Further reading:

Politicians calling for the bureaucracy to be purged of liberals, using state power to punish company’s stances on LGBT rights, threatening companies that voice support for African American voting rights. It’s a movement. (The Washington Post)

A familiar scenario:

“Conscience is but a word that cowards use,

Devised at first to keep the strong in awe.

Our strong arms be our conscience, swords our law.” — William Shakespeare (Richard III, Act V, Scene 6)

🎧 Real Dictators explores the hidden lives of history’s tyrants, fusing immersive, dramatic storytelling with interviews with world-renowned experts. The voices of historians sit alongside an array of regime insiders such as Jang Jin-sung – a former psychological warfare officer for Kim Jong-il – and François Benoit, a survivor of ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier’s reign of terror.

📚 Successful Leaders Aren’t Bullies presents actual bullying cases author Matt Paknis has experienced and addressed in the workplace with clients over the past 26 years. It empowers good leaders to choose leadership and to understand the benefits of leading with healthy behaviors and to intervene and to stop bullying. It will inspire and mobilize bullied victims to overcome and to thrive by presenting examples of resilient and healthy individuals and organizations.

There’s so much to learn,

Thanks for rousing understanding in such cool ways. Fear indeed. False evidence acting real.