A World in Time

Remembering a timeless leader

“History is our inheritance. He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living hand to mouth.”

— Goethe

Almost exactly two years ago, I set aside space to mourn the loss of one of my heroes, David McCullough (“A Larger Way of Looking at Leadership”).

While mortality is something I’ve touched on here (“On the Shortness of Life”) — specifically as it relates to a leader’s legacy — it’s not something I dwell on.

However, the passing of another hero of mine means flirting with the idea of a morbid biennial tradition. Alas, it could not be avoided.

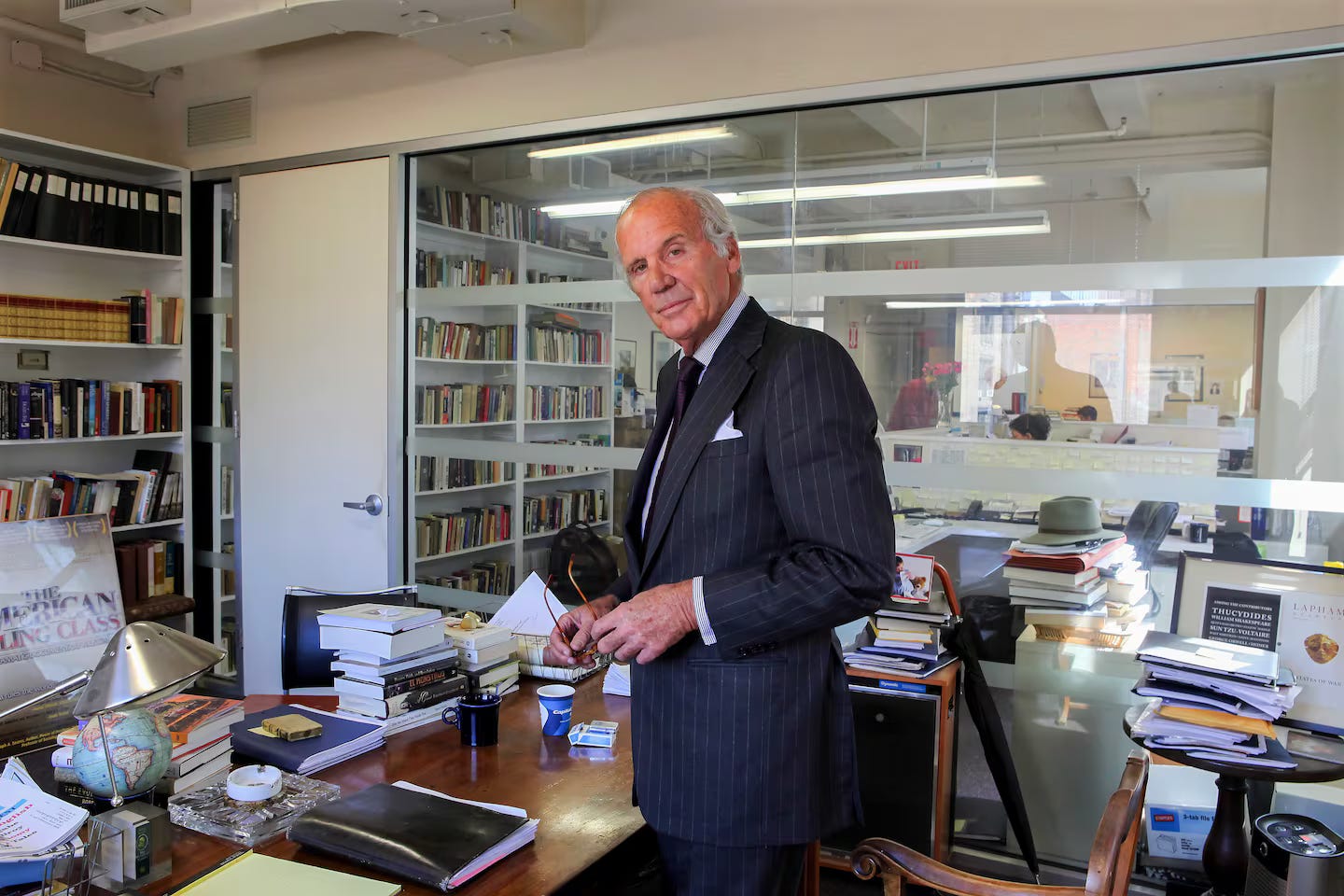

Lewis H. Lapham passed away on July 23 at the age of 89. He was editor of Harper’s Magazine for nearly three decades, first from 1976–1981 and then 1983–2006, at which time he assumed the title Editor Emeritus. In 2008, he founded Lapham’s Quarterly, which he edited until his death.

The name Lewis H. Lapham may not be immediately familiar to the larger public, but to the world of magazines, editors, and those interested in history and literature, he was a transmuter of stories, a leader of thinking, a teacher of lessons.

“To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child,” wrote Marcus Tullius Cicero. And in that regard, Lewis H. Lapham was in the business of child-rearing.

“We have less reason to fear what might happen tomorrow than to beware of what happened yesterday. I know of no better reason to read history. Construed as a means instead of an end, history is the weapon with which we defend the future against the past.”

— Lewis H. Lapham, 2008

He wanted to educate and inspire the civic mind as well as the intellectual mind. “Children unfamiliar with the world in time make easy marks for the dealers in fascist politics and quack religion,” he wrote in 2008.

A timeless (and timely) observation.

A Writer’s Writer

Some leaders make you want to be better simply by their presence. Lewis H. Lapham was one of those people. Indeed, his writing was inspirational.

His Washington Post obituary called him “a strong and reliable narrator with a singular talent for metaphor.”

As a writer, every time I found myself reading a Lewis Lapham column or book, his style inspired me to elevate my craft.

With elegance and grace, he cannily fused the timeless elements of history and literature with the struggles and foibles of modernity, taking the reader on a thoroughly enjoyable journey of poetic and majestic prose, reminding us that we are part of a larger tapestry of life on this planet.

His essays — a number of which are excerpted below — allowed readers to consider a larger view than the narrowness of our own limited thought bubbles.

“Our ignorance of history causes us to slander our own times.”

— Gustave Flaubert, 1871

A Timeless & Timely Quarterly

Our collective historical amnesia is not a modern scourge. Indeed, early in his tenure at Harper’s, Lapham admitted “I soon discovered that I had as much to learn from the counsel of the dead as I did from the advice and consent of the living.”

And so he developed Lapham’s Quarterly, which he succinctly described as “the Great Books made topical.”

He expanded on that concept in his first preamble — the lead essay in the Winter 2008 issue:

“To bring at least some of the voices of the past up to the microphone of the present, Lapham’s Quarterly chooses a topic prominent in the news and, within the perimeter of that topic, assembles a set of relevant texts—literary narrative and philosophical commentary, diaries, speeches, letters, and proclamations, as well as essays and reviews by contemporary historians. The method assumes that all writing, whether scientific treatise, tabloid headline, or minimalist novel, is an attempt to tell a true story… I know of no task more difficult, but it is the joint venture entered into by writer and reader—the writer’s labor turned to the wheel of the reader’s imagination—that produces the freedoms of mind from which a society gathers its common stores of energy and hope.”

Each issue of the Quarterly focused on a single timeless theme — such as education, religion, death, time, disaster, happiness, technology — by assembling extracts from great works of history and literature, from ancient to modern, together with a handful of essays from respected writers.

A Voice in Time

Last year, I asked him to join me on the Timeless Leadership podcast, but Lapham demurred, citing his lack of expertise in the field of leadership:

“I appreciate your kind note, but I'm not the best person to talk about leadership. I think I sometimes know it when I see it in a football coach or baseball manager, but I have little or no idea what the word means when awarded to politicians, Hollywood celebrities, and corporate overlords. We live in a society afraid of speaking freely, adept at the art of going along to get along, content to kiss the hand and lick the boot of money.

“I would that it were otherwise and I’m sorry that I can’t send more welcome news.”

Even a simple email from Lapham was elegant.

However, he was more modest in his self-assessment than he ought to have been. I later found this quote from him:

“Leadership consists not in degrees of technique but in traits of character; it requires moral rather than athletic or intellectual effort, and it imposes on both leader and follower alike the burdens of self-restraint.”

In my estimation, he had essential skills that every good leader should have: he was widely read, could see and understand trends and draw a throughline through history to put them in perspective, he communicated exquisitely, and he had a wonderful and wry sense of humor.

You can hear his deep resonant baritone as he reads his satirical essay of A Christmas Carol:

Useful, Beautiful, True

In a world of bits and bytes where attention is measured in fractions of a second and imprimaturs are bestowed with thumb-swipes and emoji, and where we rely on AI to think for us, long-form content might seem to be as en vogue as high-button shoes or parachute pants.

But with Lewis Lapham, who won the National Magazine Award for exhibiting “an exhilarating point of view in an age of conformity,” we are reminded that while the internet offers us content as readily available and as dubiously nutritious as fast food, our greater selves sometimes require a more substantial feast pro mente.

“It isn’t with magic that men make their immortality. They do so with what they’ve learned on their travels across the frontiers of five millennia, salvaging from the ruin of families and the death of cities what they find to be useful or beautiful or true. We have nothing else with which to build the future except the lumber of the past—history exploited as natural resource and applied technology, telling us that the story painted on the old walls and printed in the old books is also our own.”

Keep telling your stories. Make them useful, or beautiful, or true.

Or all three.

Ave atque vale.

There’s so much to learn,

Offer:

I have some spare copies of Lapham’s Quarterly I’m giving away. If you are a member of our Ampersand Guild (paid subscribers) or if you become one today, and you would like one, please leave a comment.

Some Lapham Excerpts

Lapham’s essay titles were clever without being cloying. The essays themselves were mini-masterclasses on a single topic, considered carefully and deeply by an intellectual who had examples at his fingertips from the world in time.

His inaugural essay for Lapham’s Quarterly (“The Gulf of Time”) acknowledged the impact of humanity and reflected on the importance of at least a passing familiarity with our historical record:

“The figures in the dream have left the signs of their passing in what we know as the historical record, navigational lights flashing across the gulf of time on scraps of papyrus and scratchings in stone, on ships’ logs and bronze coins, as epic poems and totem poles and painted ceilings, in confessions voluntary and coerced, in five-act plays and three-part songs.”

Education was a perennial concern of Lapham’s, and in “Playing With Fire” he critiqued the state of education in America in 2008. Then as now, the framework of American education held fast to the ardent but mistaken belief that education is a commodity, the stuff that one pours into empty vessels in a system geared toward post-graduate placement rather than the accumulation of knowledge — a purely transactional exchange at the academy:

“Students don’t go to school to acquire the wisdom of Solomon. They go to school to acquire a cash value and improve their lot, to pick up the keys to the kingdom stocked with the treasures to be found in a BMW showroom or an Arizona golf resort. Their education bears comparison to the procedure for changing caterpillars into silkworms just prior to their transformation into adult moths. Silkworms can be turned to a profit; moths blow around in the wind, and add nothing to the wealth of the corporation or the power of the state.”

“Captain Clock” is set in 2014, but it timeless in its view of how we treat the commodity of time — from overtime to downtime, spending time to saving time, the uses and abuses of our minutes and days:

“Tardiness is next to wickedness in a society relentless in its consumption of time as both a good and a service—as tweet and Instagram, film clip and sound bite, as sporting event, investment opportunity, Tinder hookup, and interest rate—its value measured not by its texture or its substance but by the speed of its delivery, a distinction apparent to Andy Warhol when he supposedly said that any painting that takes longer than five minutes to make is a bad painting.”

In 2013, a full decade before his eventual death, Lapham contemplated the great inevitable in “Memento Mori”:

“My body routinely produces fresh and insistent signs of its mortality, and within the surrounding biosphere of the news and entertainment media it is the fear of death—24/7 in every shade of hospital white and doomsday black—that sells the pharmaceutical, political, financial, film, and food product promising to make good the wish to live forever.”

A good writer is also a good reader, and Lapham reveled in the infinite voyages of discovery — of the world and of self — he found in books (“Homo Faber”):

““Read to live,” says Flaubert somewhere in his letters, and I take him at his word. Books I regard as voyages of discovery, and with an author I admire I gladly book passage to any and all points of view or destination—to Rome during the lives of the Caesars, to Shakespeare’s London, to Berlin and Harlem in the 1920s. I don’t go in search of the lost gold mine of imperishable truth. I look instead to find the present in the past, the past in the present. To discover within myself the presence of a once and future human being.”

In his first inauguration in 1933, Franklin Roosevelt warned us that the only thing we had to fear was fear itself. In 2017 “Petrified Forest,” Lapham made it clear that fear was front and center:

“Fear itself these days is America’s top-selling consumer product, available 24-7 as mobile app with color-coded pop-ups in all shades of the paranoid rainbow. Ready to hand at the touch of a screen, the turn of a phrase, the nudge of a tweet… Diligently promoted by the news and fake news bringing minute-to-minute reports of America the Good and the Great threatened on all fronts by approaching apocalypse—rising seas and barbarian hordes, maniac loose in the White House, nuclear war on or just below the horizon… Our schools and colleges provide safe spaces swept clean of alarming, unjustified speech, credit a rarefied awareness of nameless, unreasoning terror as evidence of superior sensibility and soul.”

Memorials

Lewis H. Lapham | 1935–2024 (Lapham’s Quarterly)

Lewis H. Lapham, Harper’s Editor and Piercing Columnist, Dies at 89 (The New York Times)

Lewis Lapham knew that a great editor was an artful thief (Washington Post)

Lewis Lapham Salvaged From History What Was Useful, Beautiful, and True (The Nation)

Rest in Peace, Lapham (The American Conservative)

The End of an Era (Harper’s Magazine on Substack)

More on Lewis Lapham (The American Bystander)

On the Remarkable Legacy of Lewis Lapham (LitHub)

Other pieces featuring Lapham

The Art of Editing No. 4 (Paris Review)

The complete Preambles (Lapham’s Quarterly)

Lapham’s collected work for Harper’s (Harper’s Magazine)

Lewis Lapham on Forty Themes | Roundtable (Lapham’s Quarterly)

Lewis Lapham: What I Read (The Atlantic)

Rookie Reporter: Lapham tells of his experience as a cub reporter at the San Francisco Examiner (The Moth)

A Selection of Lewis Lapham’s Works

Age of Folly: America Abandons its Democracy (2016)

Gag Rule: On the Suppression of Dissent and Stifling of Democracy (2004)

Lapham's Rules of Influence: A Careerist's Guide to Success, Status, and Self-Congratulation (1999)

Waiting for the Barbarians (1997)

Hotel America: Scenes in the Lobby of the Fin de Siecle (1995)

Money and Class in America: Notes and Observations on Our Civil Religion (1988)

Remembrances of Lewis Lapham in the Revitalized Lapham’s Quarterly

The Finch Interested Me by Donovan Hohn (June 13, 2025)

The Jazz Way by Ben Metcalf (June 14, 2025)

Salvage Artist by Kelly Burdick (June 16, 2025)

The Fifth Act by Elias Altman (June 18, 2025)

The Spendthrift Muse by Curtis White (June 26, 2025)

All Good Editors Are Pirates by Kira Brunner Don (June 27, 2025)

Motet for the Record by Henry Freedland (July 22, 2025) — a beautiful curation of Lewis Lapham’s style and voice

I am sorry for this loss that is profoundly personal to you. I love your regular use of Lewis Lapham quotes as that is how I know him at all. I love the insight that history is a weapon which we use to defend the future against the past. We are doing it now!!

For my Costa Rica writers group this week, we wrote our own eulogies which got me thinking about mortality. I started with the Lorax lawyer is dead- the work I want to be remember for and of course covered my marriages and motherhood and grandmother hood and gave quotes I always say that are wise and perhaps entertaining. Even as I wrote as another person speaking about me, I ended appreciative of my friends that went before me and told the potential mourners how I am likely hanging out with them since my people need comforted.

I don’t think of myself in terms of leadership and find it a bit odd that I joined your newsletter even before Substack was invented or before newsletters were fully appreciated as a way to grow a following. You just have the messages I am meant to hear as I continue to find my ways of service. Thank you and thanks for bringing Lewis H Lapham and his wisdom, combined with yours, into our lives.