I’ve lifted the paywall on this essay from the Archives; reading and writing matter, and I’d like as many people as possible to absorb this.

If you’re one of them, please join us on the regular:

“When you reread a classic, you do not see more in the book than you did before; you see more in you than there was before.”

— Clifton Fadiman

Academics are still on my mind this week, after discussing the humanities with you last week.1

This is more than an academic discussion (pun intended). Lifelong learning and curiosity are two of the hallmarks of great leaders―individuals who are constantly consuming information in a variety of formats, who then take what they’ve learned and weave it into a tapestry of other formats that complement their teams’ styles.

But you may have noticed that the preferred medium of communication in the last few months has skewed toward video, as we sit in front of webcams and partake in meeting after meeting on Zoom.

Video is powerful because it involves so many of our senses, but it’s also the most exhausting precisely because it involves so many of our senses.

Zoom fatigue is real―and it has a long history.2

Littera Scripta Manet

Writing is still the most powerful medium that we have, and the best leaders are also good writers; arguably, communication is probably the most essential skill a leader can have.

Everything else―strategic planning, hiring, creating a vision, motivating your team, and even financial planning―involves communication, which is simply defined as a process for exchanging information.

“What magnifies a voice is the force of mind and the power of expression, which is why Shakespeare’s plays still draw a crowd in Central Park, and why we find the present in the past, the past in the present, in voices that have survived the wreck of empires and the accidents of fortune.”

— Lewis H. Lapham, 2008

Good communication makes all the difference in how your audience receives your information. Whether it’s relayed in a story or a set of bullet points, leaders need to present their ideas in ways that inspire, motivate or emphasize, and you can't do that without spending time laying it all out in your mind.3

“Writing is thinking. To write well is to think clearly. That’s why it’s so hard.”

— David McCullough, 2002

Perhaps this is why exhaustion is setting in from our video calls. Because just sitting down in front of a camera and talking doesn't require planning. Set up the shot, hit “Join Call” and start talking.

Compare that to a planned video shoot, where you’re blocking every shot and have a script to follow.

A script? Why, that’s writing!

So even for video (good video, that is), writing is necessary. It’s also the secret to giving a good presentation―writing out what you plan to present helps frame the idea and the persuasiveness before they come flowing from your mouth.

“Vox audita perit, littera scripta manet.” (“The spoken word vanishes; the written word remains.”)

― Latin proverb

With live presentations, our interactions are ephemeral. They remain in our memories, but are inconveniently inaccessible.

Think of all of the great actors of the past who were heaped with praise by critics: Edwin Booth, David Garrick, Richard Burbage, and more. Yet there’s no one alive who can convey what the experience was like, the nuances of the craft, or how it made them feel.

With video, thanks to YouTube, the second largest search engine on the internet, we have the ability to scan, search, and find material that is buried in our memory. But it can be hit or miss. The written word, not so much.

We have a record of great acting and great speeches from the last century that have been captured on film or audio, but there have been great speeches throughout history worthy of remembering.

How do we know? They were written down.

One of the reasons we still have the Iliad and the Odyssey with us today is because they transitioned from the oral tradition to the written record.

It’s not enough to simply write things down; after all, we can still read the graffiti on the walls of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Words and ideas will remain with us if we’re appropriately inspired—that is, if they’re crafted in a way to make us sit up and pay attention.

“There is nothing so intolerable as dull writing.”

― Charles Honce

If you want to become a great leader, you first need to become a good writer. What’s the secret to good writing? If you want to be a good writer, first you need to be a reader.

Don’t miss this from our Archives:4

Preparing to Write

“The greatest part of a writer’s time is spent in reading, in order to write: a man will turn over half a library to make one book.”

― Samuel Johnson, 1775

Reading is a way to expand our minds, to introduce ourselves to concepts and faraway lands that we might never otherwise discover. And sharing what we learn from our reading is a gift — a gift to ourselves and a gift to share with others through our insights.5

For me, the most intense and rewarding part of writing this newsletter isn’t the writing. Nor is it the feedback (although I do appreciate hearing from you!). It’s the research. I usually put five times the time and effort into reading and research that I do into the writing of my newsletter.

How are you preparing for what you write?

“It is what you read when you don’t have to that determines what you will be when you can’t help it.”

― Rev. D.F. Potter, 1927

Certainly, you should be educating yourself with analyst reports, memos, and industry news, but there are sources outside of your vertical that will give you inspiration and insights where you least expect them.

For example, I was recently reading Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Morituri Salutamus,” a poem he composed for the 50th anniversary of Bowdoin College’s class of 1825. 6

In it, Longfellow laments the inexorable march of time, but indicates that we can use age to our advantage—for with age, we gain insights that are simply unachievable in youth.

The scholar and the world! The endless strife,

The discord in the harmonies of life!

The love of learning, the sequestered nooks,

And all the sweet serenity of books;

The market-place, the eager love of gain,

Whose aim is vanity, and whose end is pain!But why, you ask me, should this tale be told

To men grown old, or who are growing old?

It is too late! Ah, nothing is too late

Till the tired heart shall cease to palpitate.

Cato learned Greek at eighty; Sophocles

Wrote his grand Oedipus, and Simonides

Bore off the prize of verse from his compeers,

When each had numbered more than fourscore years,

And Theophrastus, at fourscore and ten,

Had but begun his “Characters of Men.”

Chaucer, at Woodstock with the nightingales,

At sixty wrote the Canterbury Tales;

Goethe at Weimar, toiling to the last,

Completed Faust when eighty years were past.

These are indeed exceptions; but they show

How far the gulf-stream of our youth may flow

Into the arctic regions of our lives.

Where little else than life itself survives.

There are two points here for business leaders that are worth reflection.

The first is we ought to give more consideration to hiring older employees, who will have more experience and insight to apply to our business challenges, rather than relying on cheaper labor that will make mistakes that the more experienced workers could have avoided.

The bean-counters will push us to hire in ways that will immediately protect the bottom line, but in certain cases, these decisions will have longer-lasting impacts if we fall into the same traps we once did (see above: “we find the present in the past, the past in the present”).

Concurrently, the median tenure of employees at companies is 4.2 years7, meaning that in addition to being prone to hiring workers with less work experience, we're victims to a shrinking institutional memory as well.

The second breadcrumb that Longfellow leaves us is to continue to read—and reread—long after we’ve left school. That Fadiman quote at the beginning of the essay is a reminder that what we get out of books is almost mathematical in its precision: as we grow, so does our understanding and interpretation of what we read.

In the very first essay for Lapham’s Quarterly in 2008, Lewis H. Lapham noted this phenomenon:8

“As a college student, I acquired the habit of reading with a pencil in my hand, and, in books that I’ve encountered more than once, I discover marginalia ten or forty years out of date, most of it amended or revised to match a change in attitude or plan.”

How much do our attitudes or plans change over time? Are we even willing to admit it? This kind of flexibility speaks to our fallibility―something certain leaders seem to be afraid to admit.

But those with emotional intelligence are naturally open to listening to others, taking in new information, and applying it to their decisions. With age, experience, and observance of our inevitable errors, we find how necessary reflection is.

Reflection can come in a variety of forms, whether it's through meditation, journaling, or even reading. But rarely (if ever) does it happen during a string of video calls.9

Read more. You’ll discover a world within you and around you taking on a whole new meaning ― and you can share it with those who matter to you.

“When you sell a man a book, you don’t sell him 12 inches of ink and glue―you sell him a whole new life.”

― Christopher Morley

“The only end of writing is to enable the readers better to enjoy life or better to endure it.” ― Samuel Johnson

I.

It’s not just Zoom that’s giving us trouble as we try to remain connected with family, friends and colleagues by spending more time online. How do we break the cycle that ties us to the screen? I Cured My Social Media Addiction by Reading Books. (Forge)

II.

If you’re absolutely wiped after a day of video calls, you’re not alone. There’s a reason Zoom calls drain your energy. (BBC)

III.

With so much vitriol and needless bickering online, there’s a place you can go to escape it all (as long as you aren’t an editor on the site). Wikipedia: The Last Best Place on the Internet. (Wired)

“The more I read, the more I acquire, the more certain I am that I know nothing.” ― Voltaire

I.

In 1345, Richard de Bury wrote of the power of books to transport him: “In books I find the dead as if they were alive; in books I foresee things to come; in books warlike affairs are set forth; from books come forth the laws of peace. All things are corrupted and decay in time; Saturn ceases not to devour the children that he generates: all the glory of the world would be buried in oblivion unless God had provided mortals with the remedy of books.” (Philobiblon)

II.

The difference between good writing and bad writing often comes down to the skill of an editor. The earliest editors were called correctors, and their work wasn't always appreciated, as “they usually found themselves the objects less of gratitude than of anger, pity, or derision.” (Lapham's Quarterly)

III.

In Literary Life in a Plague Year, a photo essayist takes a stroll through Washington, D.C. in the spring of 2020, finding that during the pandemic, the city was devoid of its usual human activity related to books: “The absence of a tactile literary culture—one that happens in real time rather than on a screen—meant an uncomfortable cultural silence.” (Virginia Quarterly Review)

“If we let ourselves, we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work. The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavorable. Favorable conditions never come.” — C.S. Lewis, 1939

🎧 In BiblioFiles, the CenterForLit staff embarks on a quest to discover the Great Ideas of literature in books of every description: ancient classics to fresh bestsellers; epic poems to bedtime stories. This podcast is a production of The Center for Literary Education and is a reading companion for teachers, homeschoolers, and readers of all stripes.

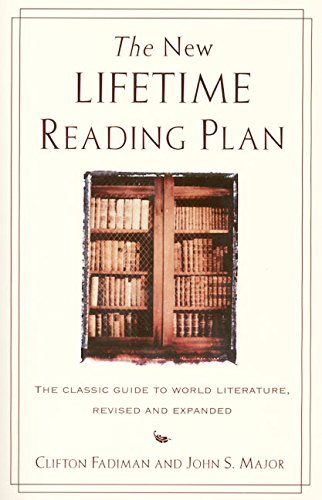

📘 The New Lifetime Reading Plan by Clifton Fadiman brings this classic book back to print after 40 years. It provides readers with brief, informative and entertaining introductions to more than 130 classics of world literature. From Homer to Hawthorne, Plato to Pascal, and Shakespeare to Solzhenitsyn, the great writers of Western civilization can be found in its pages. In addition, this new edition offers a much broader representation of women authors, such as Charlotte Brontë, Emily Dickinson, and Edith Wharton, as well as non-Western writers such as Confucius, Sun-Tzu, Chinua Achebe, Mishima Yukio, and many others.

Thanks, and I’ll see you on the internet.

Perception, imagination, and insights come from years of experience on the job, but they also come from being widely read and learning how to think critically.

These are attributes that are a consequence of an education in the humanities.

What Comes After Zoom Fatigue? Vox, July 17, 2020

The David McCullough quote is sourced from an interview with NEH chairman Bruce Cole, Humanities, July/Aug. 2002, Vol. 23/No. 4

I’ve lifted the paywall on this essay from the Archives because I can’t stress enough the power and importance of reading in your development as a person. Also, don’t miss the photo of one of the most amazing home libraries you’ll ever see.

Another must-read from the Archives. When you read, are you a receptacle or a collaboratory? How are you sharing your gift?

Incidentally, the title of the poem is taken from the old Latin phrase “Nos morituri te salutamus,” translated as “We who are about to die salute you.” This is the apocryphal phrase that gladiators were supposed to have uttered to the emperor before battle.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 2018

It’s well worth reading “The Gulf of Time” in total, which is a wonderfully written piece by a well-read writer.

That link is a whole section of essays on the topic of reflection here on Timeless & Timely. Worth bookmarking.