“Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.” — Robert Ingersoll, 1883

One of the stern lessons of childhood (mine, at least — maybe yours too) my parents drilled into me was: always try to do the right thing, even when it’s hard.

Typically, the more difficult scenarios involved making a decision to do what was right when my friends tempted and lured me in other directions.

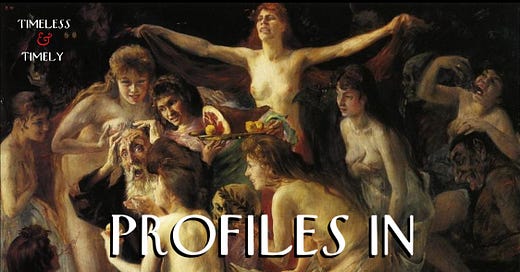

Temptation is a shapeshifter, ranging from timeless vices like lust, greed, and gluttony to modern manifestations such as manufactured psychedelics, peer pressure, and doomscrolling through the news.

It can be hard to do the right thing when we’re tempted to do otherwise. And in that moment, it’s easy to forget how consequential your words and actions are when you’re a leader.

Leaders — people in power — are watched closely, their every decision and utt…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Timeless & Timely to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.