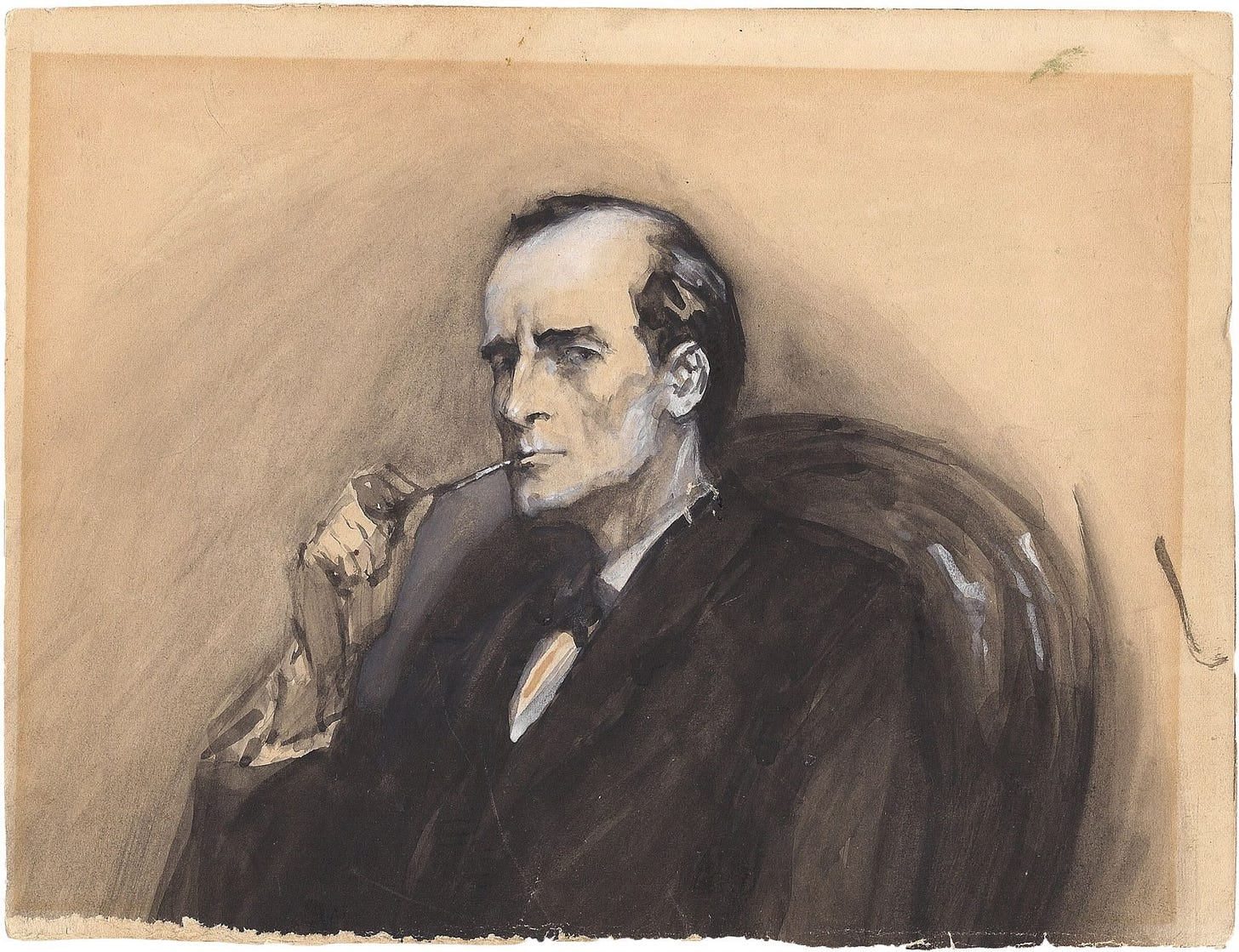

“You know my method. It is founded upon the observation of trifles.” — Arthur Conan Doyle, 1891

Timeless & Timely has audio versions of the posts for you to enjoy. They are available to Premium subscribers. This one is available here:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Timeless & Timely to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.