How Much Is Enough?

Insatiable desires lead us down a path that may be lonely at the end

“I am indeed rich, since my income is superior to my expense, and my expense is equal to my wishes.”

— Edward Gibbon, 1776

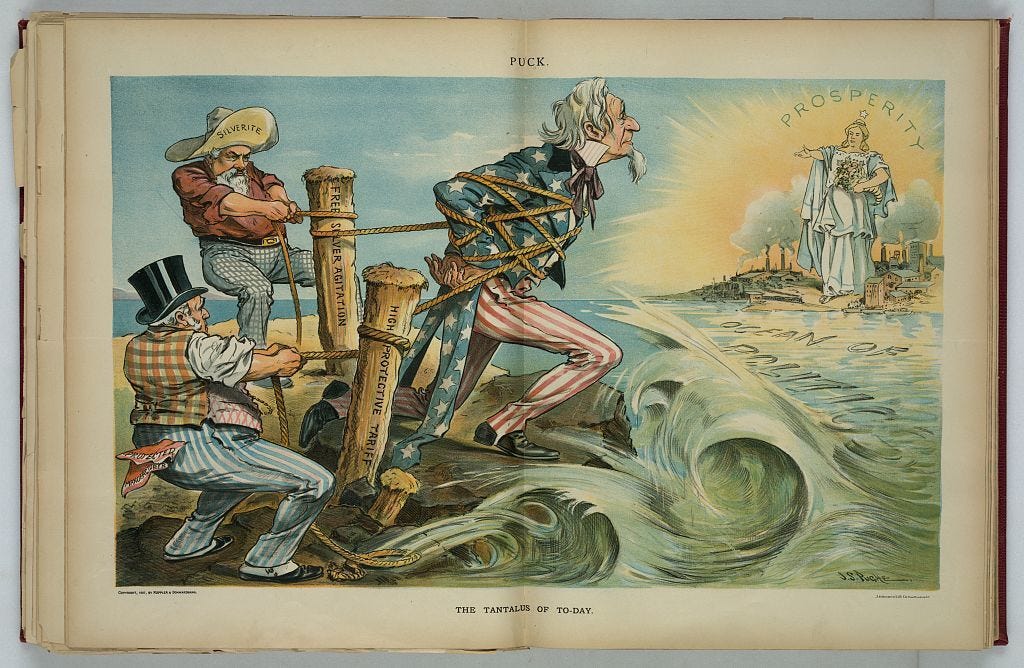

Tantalus had everything going for him.

He was the legendary king of Sipylus, a son of Zeus and Pluto, famous for his immense wealth, like Midas and Croesus.

But, like some people of privilege, too much simply wasn’t enough.

Tantalus was welcomed to Zeus’ table on Mt. Olympus—a great honor for a mortal. But he abused Zeus’ hospitality by stealing ambrosia and nectar and brought them back to his people to make them immortal and reveal the secrets of the gods.

Then, he offered up his son Pelops as a sacrifice, cutting him into pieces, cooking him, and serving him to the gods to test their powers of omniscience. When they discovered Tantalus’ treachery, the gods punished him with an eternal sentence befitting his offenses.

Tantalus was forced to stand in a pool of water, chained underneath a fruit tree with low branches, for eternity. Every time he reached for a piece of fruit, the branches rose beyond his reach; every time he bent to quench his thirst, the water receded.

As you know, the English word “tantalize,” meaning to tempt or torment with the sight of something desired but out of reach. For Victorian or Edwardian antique hunters, the tantalus is a wooden rack of decanters secured by a lock; the idea was that servants would be unable to enjoy the nectar of their employers.

The Ancient Greeks knew it, Victorian British knew it, and it’s still true today: show us something that we don’t yet have, something that might be within our reach, and we will try to attain it, even if we already have everything we need.

How often do we find ourselves in a situation, wishing we had more or better? We tell ourselves “if only.”

If only I had a better salary, I’d feel secure. If only I had a bigger house, I’d be content. If only I got that promotion, I’d be happier.

If only… If only…

We seem to predicate how we feel and how we live our lives based on tangibles and outcomes. As if there were some end goal, some final state of being that we could attain if we possessed something or passed a level—an IRL version of “Achievement unlocked!”

If you have desires that are then satisfied—more money, a different house, a different job, a vacation, an ice cream cone, a single malt whisky—does that keep you happy and satisfied? Likely not. Your circumstances change briefly, but then you find you’re back to saying “if only…” again.

From Sacrifice to Elegance

The Jimmy Carter era was a short stretch of American history blighted with long gas lines, a 55 mph speed limit (for fuel economy more than safety), and a cardigan-wearing president who, in February 1977, advised Americans to set their thermostats at 65°F in the daytime and 55°F at night to sacrifice for their fellow citizens.

The Reagan era ushered in “a return to elegance,” where Americans threw off the shackles of sacrifice and adorned themselves with the symbols of a new era, symbolized by stockbrokers in power ties, suspenders, and limousines.

The decade that was decorated in decadence delivered to us such cultural moments of excess as represented by the fast lanes of Jay McInerny’s Bright Lights, Big City and the “Greed is good” speech in Wall Street.

“Greed is good” equates to “more is better,” and before you know it, Americans were encouraged to pursue happiness, one of the triptych of unalienable rights granted to them in the Declaration of Independence.

That founding document was written at a moment of great upheaval for the country, when our well-read forbears understood human nature and knew history deeply.

It is precisely at moments of change—a new job, a new house, democracy under threat, or some other significant event—when we should consider what fulfills us and more importantly what our responsibility is to those around us, rather than what we might have more of.

“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

— Corinthians 13:11 (KJV)

Does the consumption of more or the process of acquisition blind us to other priorities? Does it make us oblivious to the needs of others, or cause others to see us as callous in the face of suffering?

Look, it’s fine to chase things that bring us joy, in whatever form that might take. Like the saying goes, “Money can’t buy happiness. But it can buy ice cream, and that’s basically the same thing.”

The question is, how much ice cream is enough?

“We reach. We grasp. And what is left in our hands at the end? A shadow. Or worse than a shadow—misery.”

— Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1926

There’s so much to learn,

In Friday’s edition for our Ampersand Guild members, we look at the intersection of abundance, boredom, and choice:

Oooh, good one. And thanks for the coin! Looking forward to Friday's missive.