“Nobody, who has not been in the interior of a family, can say what the difficulties of any individual of that family may be.” — Jane Austen, 1815

When it comes to succession, many family businesses give deference to the second generation of their family, whether or not the offspring have the necessary credentials to qualify for an executive position.

When the business is against the ropes, struggling to survive, they finally come to the realization that perhaps an outsider might be worth considering. This is what Bill Ford did in 2006: he stepped down as CEO and brought in industry outsider Alan Mulally.

In It Together

Premium members can listen to this essay: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” — Abraham Lincoln, 1858 I recall a scene in the mid 1990s just after leaving Boston University: Dav…

It’s also what happened with the Brooklyn Bridge.

An Engineering Marvel

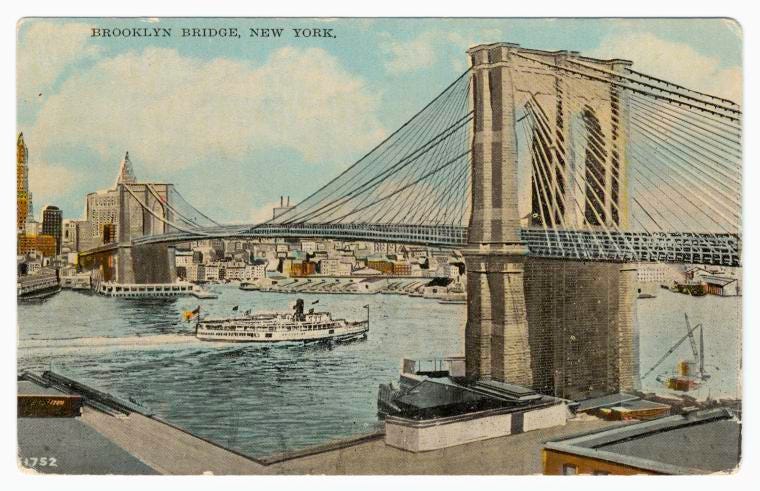

In 1883 it was hailed as the world’s greatest engineering accomplishment since the completion of the Erie Canal.

The Brooklyn Bridge was masterminded by German-born engineering genius John Augustus Roebling. He had previously architected and built suspension bridges in Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Niagara Falls, and more; he founded John A. Roebling Sons’ Company to supply the wire for his projects.

Plans for the Brooklyn Bridge received final approval on June 21, 1869. One month later, Roebling was dead.

Without his continuing guidance, his supervision, his engineering expertise, the project seemed like a bridge too far. There was only one engineer in the world who was qualified to carry on.

How that was carried out is the most remarkable story of his—or any family’s—business.

A Long Process

For nearly 250 years, New York City had been inhabited by the white man, yet no bridge had ever spanned the East River to connect Manhattan Island with Long Island. Then along came John Augustus Roebling, a German-born multifaceted genius: mathematician, philosopher, linguist, musician, and inventor. As an engineer, no one could compare to John Roebling.

So in June of 1857, when he proposed to build a bridge across the East River, the possibility was taken seriously for the first time. Authorities reasoned that if Roebling said it could be done, it could be done.

After the Civil War, in which his son Washington Roebling served for the union and distinguished himself as an engineer and a heroic fighter, the elder Roebling submitted plans for a bridge twice as long as any other bridge, ever—a bridge capable of bearing nearly 19,000 tons.

The New York State Legislature granted permission in 1867. Two years of technicalities and approvals followed, but then in June of 1869, he received the final legal clearance, and construction began.

Starting on the Wrong Foot

But two weeks later, John Roebling stood on a Brooklyn wharf surveying the locations of his main piers. As a ferry boat pulled into the dock, John tripped, and his right foot was crushed between the oncoming ferry and the slip.

He had emergency surgery within the hour. His toes were amputated, then lockjaw set in; just 16 days later, John A. Roebling, the mastermind of the Brooklyn Bridge, was dead.

As the worlds of art and science mourned his passing, his 32-year-old son, a capable engineer who had worked alongside his father, was suddenly thrust into the big shoes.

But no sooner had Roebling’s son gotten his feet under him on this enormously demanding project that he too fell ill and became partially paralyzed, unable to carry on.

Those who had put so much faith in the expertise of the Roeblings began to wonder whether this engineering marvel could be completed. Without the careful supervision of Roebling or his son, without their solutions to unforeseen issues which would most certainly arise during construction, the project might well be doomed.

But someone did arrive to keep the Brooklyn Bridge alive: an engineer accomplished in higher mathematics — perhaps the only individual in the entire world sufficiently qualified to marshal such a complex operation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Timeless & Timely to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.