“The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation… We—even we here—hold the power and bear the responsibility.”

— Abraham Lincoln, 1862

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln stood before Congress to give his annual message, quoted above. The country was in the midst of a bloody civil war and the outcome was anything but certain.

One year after the assault on the U.S. Capitol and democracy, according to an Ipsos poll Americans were inexorably split on their perceptions of the events that day.

Sun Tzu wrote “the wheels of justice turn slowly, but grind exceedingly fine.” And Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously said “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Uttered thousands of years apart, these two sentiments run parallel in their faith in mankind and in their geometric analogies. Both a wheel and an arc are curved entities. Neither is a straight line.

It is very rare that we find instant justice.

True justice is a lengthy process, as investigators need to gather facts, prosecutors require time to prepare their case, and judges deliberate with solemnity and discernment.

But our attention-lacking brains have become accustomed to the pleasures inherent in a TikTok prank, a karaoke Reel, or performative cretinism on Twitter. What chance does the glacial pacing of a federal legal proceeding have against dopamine-inducing confection that appears with the ease of a swipe of a thumb?

The further we get from January 6, 2021, the more hazy some people’s memories of the events become (although we all watched it play out on live television). The good news is there are consequences being doled out: 725 individuals have been charged in connection with it.

What the leadership of the January 6th Congressional committee is focused on next is putting the pieces together to determine some level of accountability. Because we need a reckoning if we want to move forward.

Or, as professor and historian Heather Cox Richardson puts it:

“The willingness of government officials to ignore the rule of law in order to buy peace gave us enduring reverence for the principles of the Confederacy, along with countless dead Unionists, mostly Black people, killed as former Confederates reclaimed supremacy in the South. It also gave us the idea that presidents cannot be held accountable for crimes, a belief that likely made some of the presidents who followed Nixon less careful about following the law than they might have been if they had seen Nixon indicted.”

Leadership Demands Accountability

Accountability is what any organization needs when something has gone sideways. Someone needs to step up and take responsibility. Harry Truman’s famous desk plate read “The Buck Stops Here,” and it wasn’t just lip service.

This is why we cheer on people like Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen, and see some modicum of justice in the Elizabeth Holmes verdict.

In these cases, the curtain is raised and the accusatory finger of accountability is pointed directly at someone.

A Boyhood Lesson of Responsibility

For a story of the emotional power of accountability, William Faulkner’s final novel, The Reivers (1962), holds a valuable lesson.

The book is a retrospective, told by Lucius when he was an old man. He recalled some events of his childhood in Mississippi in 1905.

He was convinced by his friend Boon Hogganbeck to “borrow” the automobile of Lucius’s grandfather, “Boss.” They added coachman Ned McCaslin to the group and headed for Memphis.

Along the way, they ran into challenges and exciting new things for an 11 year-old like Lucius, from getting stuck in a bog to visiting a brothel. And Ned traded Boss’s car for a horse to pay off a friend’s debt. If it won the race it was scheduled to run in, would mean the debt would be clear and the car would return to Ned’s possession.

The action culminated the only way it could: with Lightning, the horse, winning the race, but with Boss showing up unexpectedly.

When it came time to punish Lucius, Grandfather told Father to spare the shaving strop he was going to use on the boy. Lucius admitted his guilt and expected punishment, imploring his grandfather to get it out of the way:

“How can I forget it? Tell me how to.”

“You can’t,” he said. “Nothing is ever forgotten. Nothing is ever lost. It’s too valuable.”

“Then what can I do?”

“Live with it,” Grandfather said.

“Live with it? You mean, forever? For the rest of my life? Not ever to get rid of it? Never? I can’t.”

“Yes you can,” he said. “You will. A gentleman always does. A gentleman can live through anything. He faces anything. A gentleman accepts the responsibility of his actions and bears the burden of their consequences, even when he did not himself instigate them but only acquiesced to them, didn't say No even though he knew he should.”

“A gentleman accepts the responsibility of his actions and bears the burden of their consequences, even when he did not himself instigate them but only acquiesced to them, didn't say No even though he knew he should.”

— William Faulkner, 1962

These two quotes — the one by Lincoln at the top of this essay and the other from Faulkner — were written exactly 100 years apart. And they bookend the importance of accountability.

Leaders ought to accept responsibility for their actions and bear the burden of their consequences.

At least that’s what I wrote on the morning of January 6, 2021, before anything even happened:

Leaders Need to Be Accountable

“The buck stops here.” — Harry Truman In 1948, Harry Truman made an executive order at the risk of losing popularity: he determined that segregation within the U.S. military was illegal. It was an election year, and this decision could have cost him the presidency.

There’s so much to learn,

P.S. One more thing:

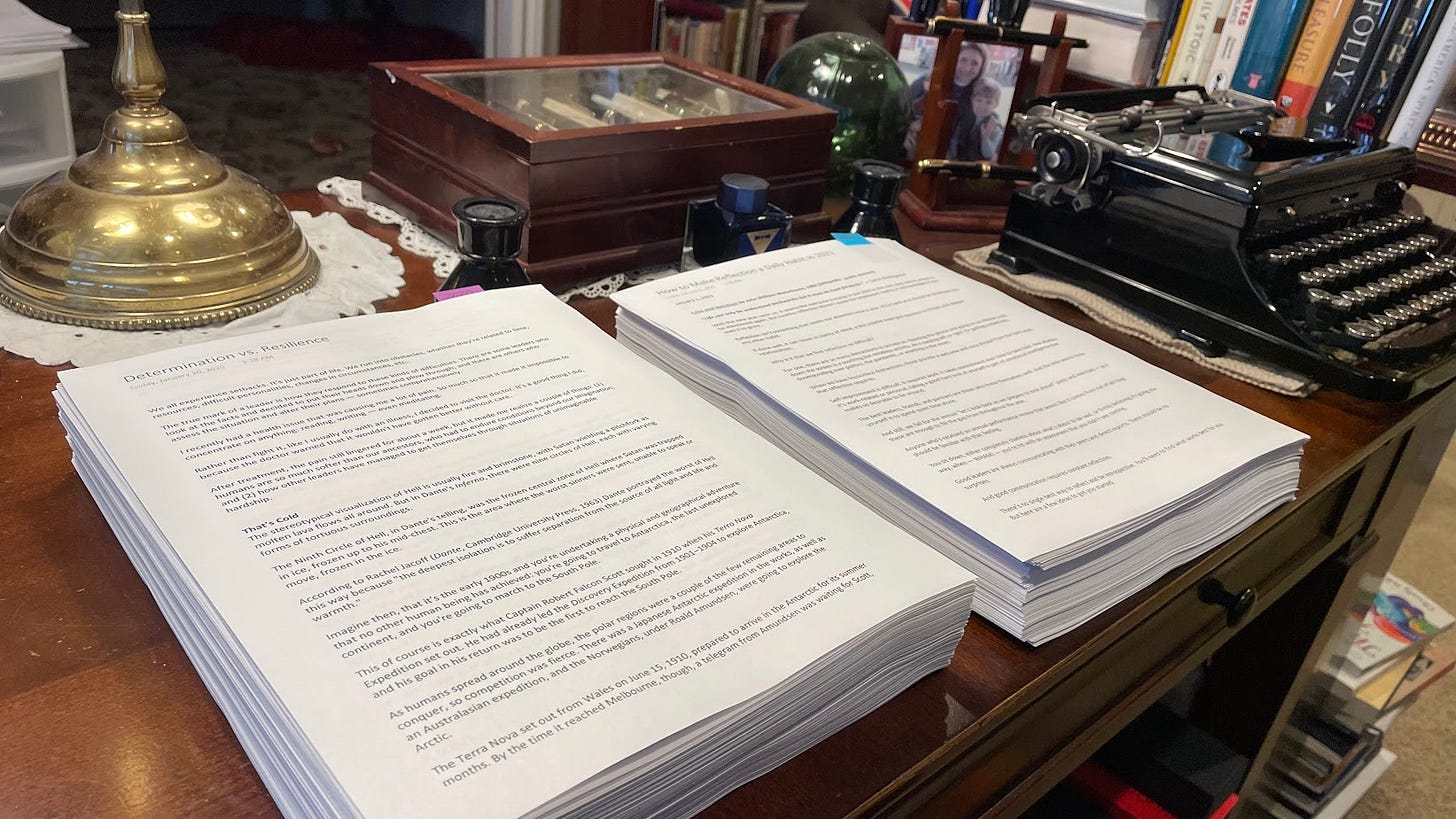

I heard from a few people who were concerned about the length of these newsletters. After printing out all of last year’s issues (335 pages) and the previous year’s (367 pages), I’m taking that into account. I always try to write just as much as a subject requires, but I recognize that not everyone has time to digest so much.

To wit, I’m going to be more succinct, particularly for paid subscribers.

And I’ll do my best to shorten the entries. No promises, though.