A Leader’s Call for Civility and Decency

Enlarged views, temperate consultations, and wise measures make up an executive's vision

“…the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of Public Liberty.” — George Washington, 1796

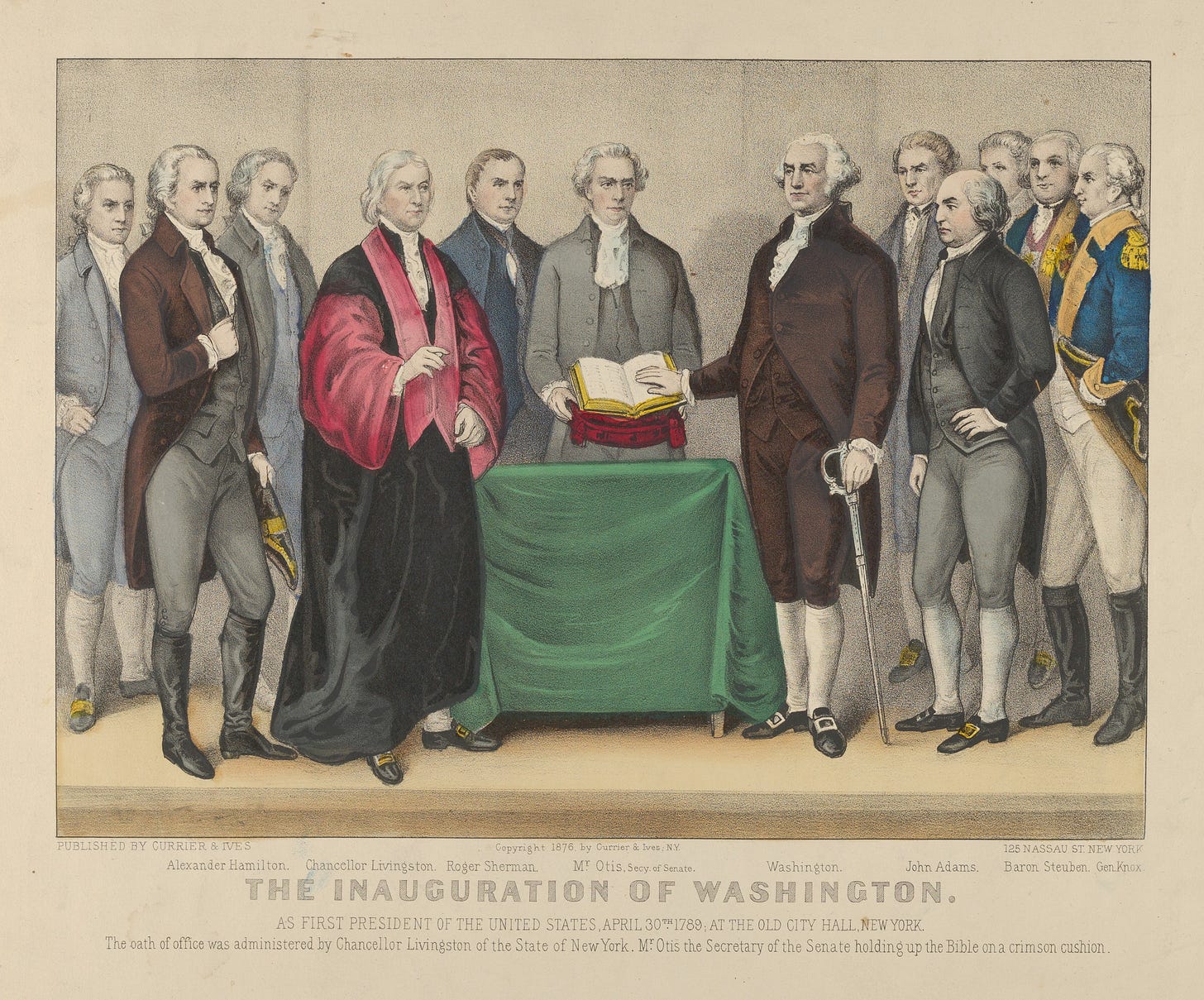

Today marks the quadrennial tradition in America when the President of the United States is sworn into office.

The job is easily the most serious and onerous one in the world; the salary is a pittance compared to the responsibilities the officeholder assumes.

All eyes are on the president on that day. All ears, too. For it has been a tradition — since our very first president — that the Commander-in-Chief delivers an inaugural address.

When George Washington accepted the presidency, he not only set the tone for future holders of that office, but he also had an opportunity to demonstrate to his country what his principles were.

“As the first of everything in our situation will serve to esta…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Timeless & Timely to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.